For brand owners in more developed markets like Europe, the primary marketing challenge to brands qua brands is from private label. This challenge comes in many forms and includes the sort of lookalike products favoured by Aldi and Lidl through to private label ranges that don’t borrow much from the original brand but compete on price, value or quality.

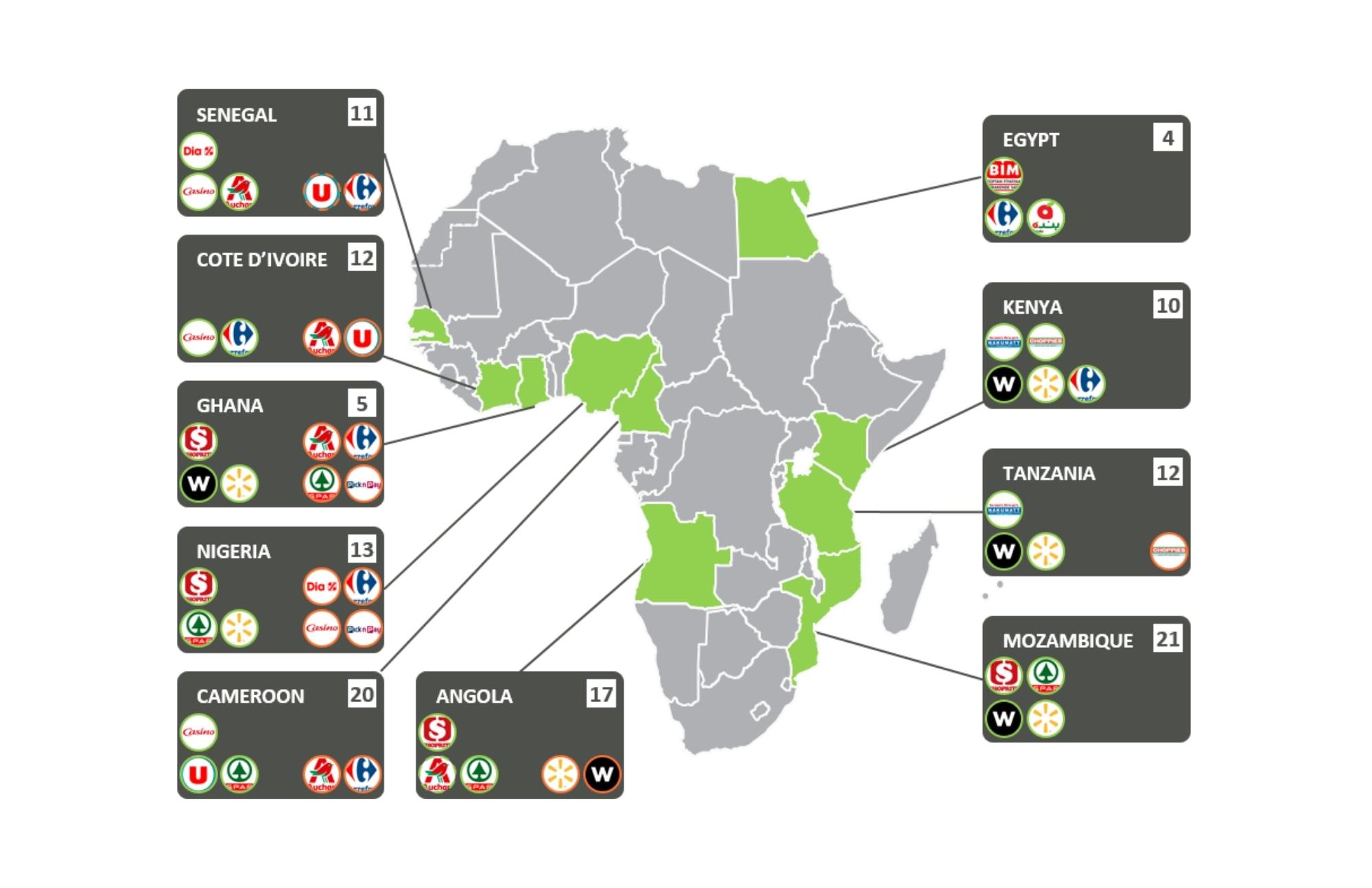

Those private label challenges increasingly exist in the Middle East with the growth of major supermarket chains such as Carrefour, Al Othaim, Panda or Lulu. They also exist in South Africa, where private label is experiencing high growth on the back of a squeeze on consumer spend and the major supermarket chains looking for new ways to improve margins.

But for most African markets, private label is relatively small because the modern trade is small and other avenues for private label growth (distributors, B2B platforms) are in the early stages of building private label portfolios.

Sweet spots

Aside private label, there are a number of other challenges to brands. These range from legal but disruptive (parallel trade) to sometimes legal but disruptive (IP theft and passing off) through to illegal and sometimes dangerous (counterfeit and adulterated products).

In fragmented markets where traditional retail dominates, the sweet spot for brands is to reach a level of penetration where the market effectively *pulls* the brand. In other words, the brand is trusted by consumers for its quality and consistency and traders seek it out because it will sell through quickly (i.e. not tie up cash flow). Few brands achieve this because of the effort and discipline it requires to create an affordable mass market product and build a distribution network capable or reaching into the lowest tiers of the traditional trade. Brands that fit this model include Indomie noodles, Dano milk, Bokomo porridge, Coca-Cola, and Omo washing powder. They are not immune from challenge, not least on price. But they are sold at a level of scale that makes pricing challenges harder in that consumers know that cheaper alternatives will likely have compromised on quality as well as being less appealing

Danger zones

The danger zone in fragmented markets comes where brand recognition is high but penetration is mid to low. A danger zone brand is still aspirational but not widely available or affordable enough. So it’s not that traders or consumers actively decide NOT to buy the leading brand. Rather, supply of a “good enough” alternative is considered satisfactory.

A risk with danger zone brands is that they are standout in their category and may end up becoming generic because of it. Three examples are Vimto (fruit cordial), Tabasco (hot sauce) and Bio-Oil (specialist moisturiser). In all three cases, the brands are aspirational, have high consumer awareness, but not necessarily penetrated enough to be considered mass market. The raft of me too brands signifies a gap in distribution and a gap in marketing (pricing too high, brand slipping from A brand to B brand), both of which are drivers of switching.

When do brand signifiers work against a brand?

A brands are not immune to the same issues if they become unaffordable or supply is disrupted. Pre-COVID-19, if you had walked into any grocery store in Addis Ababa the three big milk powder brands were Nido, Anchor and Coast. By far, Nestlé’s Nido was the market leader to the extent that if a store could only stock one brand, it would always choose Nido.

Since then a disruption of supply for Nido and Anchor has opened the door for other brands. Notably, as with the Vimto example, Nura, Hilwa and Hamda all borrow from Nido’s brand credentials. It is an example of how an A brand can be attacked and marginsalised if there is an issue that affects penetration (here, a combination of higher price and distribution).

The counter-example: Gordon’s gin in Nigeria

In Nigeria, Diageo’s Gordon’s gin has been the benchmark gin brand for decades, a legacy of the British colonial empire. Gin itself is extremely popular in Nigeria, to the extent that “gin” constitutes a broad category encompassing everything from premium London dry gin through to flavoured white spirit. Gordon’s yellow and red branding, in use for export markets, is iconic. So much so that it is referenced by local distillers for their own brands.

The figure below shows five bottles. From left to right: a 1990s era Gordon’s export bottle. Bull gin, made by Nigerian distiller Intercontinental Distillers (which traces its heritage back to the same roots as Diageo until a split in 1997). An old bottle of Chelsea gin, also made by Intercontinental Distillers. A new design for Chelsea gin. The latest Gordon’s gin branding in use in Nigeria.

The key takeaway is how Diageo has modernised key elements of the Gordon’s bottle and pack to retain its heritage but introduce new elements, such as the blue in the bottle cap, to distinguish it from cheaper me toos.

Key lessons for marketers

Availability has a reinforcing effect: the more penetration a brand has, the less room exists for me too and counterfeit products. Regular supply doesn’t just put the brand into consumer minds, it reassures them of quality, consistency and freshness.

If the brand becomes “default”, go forward not back: This sounds obvious but if a brand’s packaging, form, colour scheme becomes the signifier for the product category then if distribution shrinks, supply is disrupted or price goes too high, it opens the door for me toos.

Invest in marketing, protect trade margins: the examples above expose the gap between brand recognition and brand loyalty. In the context of traditional-oriented markets, an additional factor is trade margin. Even if consumers want a brand, if a trader makes much higher margin off a me too, it opens the door for switching.

Have a brand development plan: in some categories, such as personal care and spirits, me toos will always exist. In both cases, marketers have built up expertise of how to hold onto traditional elements of the brand design while moving it forward to mitigate the risk from me toos.