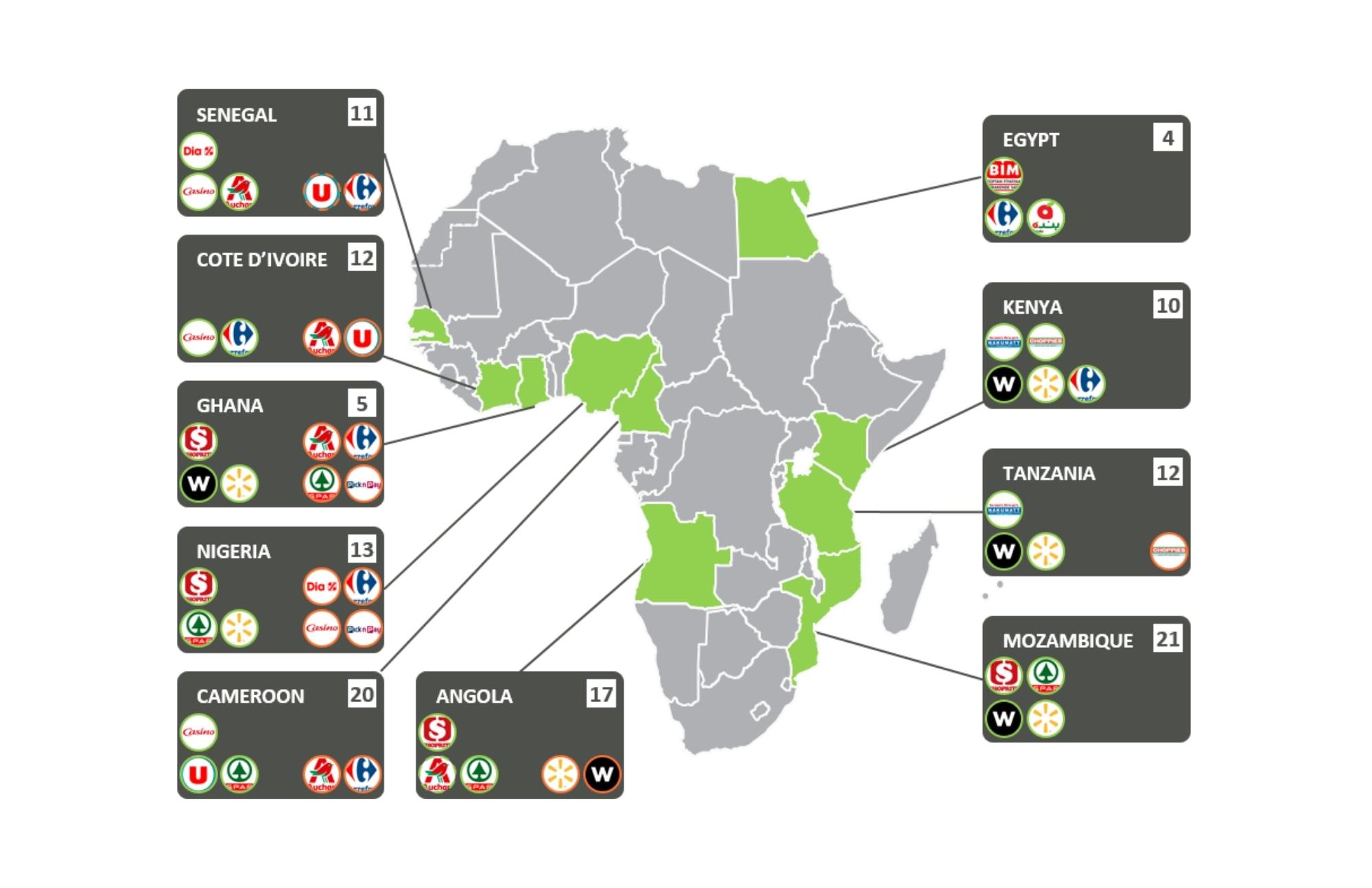

Egypt is one of Africa’s five benchmark consumer markets (South Africa, Nigeria, Morocco and Kenya) and the largest consumer market in North Africa. It has a population of around 110m and a significant middle class. It is also suffering from severe economic difficulties. This analysis will look at what the problems are and the impact for Q4 2023 and 2024.

Egypt’s foreign currency reserves fell by more than $7bn in 2022 as a result of the war in Ukraine, which pushed up commodity prices. In particular, wheat, which the Egyptian government subsidises, saw strong price rises which drained fx. Egypt will allocate EGP127.7bn ($4.15bn) for food subsidies from a budget of EGP3tn (i.e. 4.25% of its budget) for the financial year starting on July 1st 2023. The drain on fx depletes currency reserves, which in turn serves to increase the cost of borrowing.

Remittances

The World Bank forecast that remittances to Egypt would increase in 2023 by 3.1% in 2023 followed by a decline of 1.4% in 2024. In fact, during the first half of the 2022/2023 fiscal year, which falls in the second half of 2022, remittances fell by 23% to $12bn compared to $15.6bn in the year prior, according to data from the Central Bank of Egypt. This is the lowest level since the fiscal year 2016/2017. Remittances to Egypt decreased by 10% year on year to $28.3bn billion in 2022, compared to a record high of $31.5bn in 2021. To put this in context, in 2021 remittances were worth more than tourism, foreign direct investment and Suez Canal revenues, combined.

Remittances started to fall off after the first major devaluation in March 2022. The 25% difference between the official and the parallel exchange rate is a big factor, discouraging Egyptians from sending money home via official channels. Some money will be remitted informally but by its very nature is impossible to track.

Currency devaluation

Egypt has devalued its currency three times since March of 2022 in an effort to improve its trade balance. Egypt further agreed to a more flexible exchange rate in October 2022 as part of the deal for it aid package from the IMF. The official exchange rate to the US dollar is now around EGP30, down from around EGP15 to the dollar in early 2022.

In late September 2023, President Sisi, who took power after a military coup in 2013, brought forward plans for an election that was due in Spring 2024. The election will now take place in December 2023. Some Egyptians have already taken to the streets to protest his standing for a third term.

Analysts believe Sisi is bringing the election date forward because he wants voting to take place before another devaluation. The devaluation is part of a package of measures designed to address Egypt’s economic crisis and which Egypt has to undertake in order to unlock International Monetary Fund (IMF) funding.

On the 6th October 2023, Moody’s downgraded Egypt’s foreign and local currency issuer ratings to Caa1, which means its debt obligations are of “poor standing” and are subject to “very high credit risk”.

The IMF forecasts Egypt’s GDP in 2024 will be $368bn and therefore the cost of servicing external debt will will be nearly 8% of GDP. Egypt’s tax to GDP ratio is expected to be 13.5% in 2024. Egypt has to repay $29.2bn in external debt in 2024, equivalent to 85% of its foreign reserves. Until now, Sisi has managed to get support from oil-rich Gulf states but they too have tired at the pace of liberalisation.

President Sisi’s problems

Sisi’s big problem is that he is unpopular: with Egyptian voters, who can see their living standards and spending power decline; at any rate, it’s a moot point how much their vote matters; with investors, who have little interest in putting money into the Egyptian economy when the military still reaches deep into every sector.

Sisi also needs to keep on board the IMF, who are increasingly frustrated with the lack of progress towards economic liberalisation. In December 2022, the IMF approved its third program in Egypt in just over six years. That program requires unprecedented levels of transparency of the military’s business interests and requires the Egyptian government to report on the cost of the subsidies it confers on military-owned companies, which are also tax exempt.

Sisi doesn’t want to reduce the role of the military in Egypt’s economy. That involvement finances the military’s patronage networks and gives it power. Sisi needs the support of his generals, which he will lose if he cuts off their source of wealth.

Sisi also needs some legitimacy from voters, even if he has been willing to enact brutal clampdowns on protestors and political opponents. A big point of contention is Sisi’s megaprojects, costing tens of billions of dollars: the expansion of the Suez Canal, the construction of a new administrative capital in the desert, and extensive road building. In January 2023 the government ordered the postponement of projects with a large foreign currency component, as well as cuts to non-essential spending.

Complications

To complicate matters, the flare up of violence in Israel and Palestine adds more pressure although Sisi is no ally of Hamas and Egypt’s military has a long term understanding that it gets US support on the basis of toeing the line with Israel. Domestically, most Egyptians support the Palestinians which places Sisi in a more difficult position at a time when his legitimacy is already under consideration.

If Israel’s far right follows through on its promises, the prospect of up to two million Gazan refugees pouring across the border into the Sinai won’t make life any easier. Furthermore, any uncertainty in the Middle East has the capacity to push up oil prices, as has already happened.

The devaluation of the Egyptian pound had also spurred huge growth in tourism: Egypt’s tourism revenues increased by 26.8% to $13.6bn FY2022/2023, compared to $10.7bn in FY2021/2022. The number of inbound tourists increased by 35.6% to about 13.9m tourists. As at July 2023, the US government advised travellers to reconsider travel to Egypt due to terrorism. The twin prospects of a contentious election and unrest in the region may impact tourism revenues, a vital source of fx.

The impact on consumers

In August 2023, average year on year inflation rate was 37.4%. Food price inflation was about 70%. The most common word used to describe Egypt’s economy is “unsustainable.”

Moody’s has pointed to ongoing fx shortages and the lack of options the Sisi government has to fix the crisis without “exacerbating social risk”. In plain talk, it means that if the Egyptian government cuts food subsidies, people will go hungry. That week President Sisi was quoted as saying “If progress, prosperity, and development come at the price of hunger and deprivation [….] Egyptians, do not shy away from progress! Don’t dare say: ‘It is better to eat.’”

60% of Egyptians lived on or below the poverty line in 2019, before the pandemic. Labour force participation has declined over the past decade from 48% in 2013 to 42% in 2022. The female labour force participation rate is very low: just 15% in 2022, down from 23% in 2013.

For richer Egyptians, there is also a price. The Central Bank of Egypt has put new restrictions on spending abroad, including suspending the use of Egypt-issued debit cards in foreign currency. The new policy puts limits on withdrawals and purchases by credit cards abroad and is designed to halt the drain on foreign currency. The government claims that people were using debit cards outside Egypt to benefit from the difference in the exchange rate between the official and the parallel markets. Now foreign travellers have to get their fx through banks at the official rate before they travel.

The impact on FMCG businesses

At the moment, the pressures on fx show themselves in a complicated process of product registration that is designed to make it much harder for foreign FMCG companies to sell into Egypt. Pressures on fx generally also mean that importers struggle to import goods because they cannot get the dollars. In practice, in Egypt that means that distributors and companies connected to government get preferential treatment.

At the same time, like many other governments in Africa, the Egyptian government is heavily promoting domestic manufacturing and processing in sectors such as FMCG and pharma and looking to open up new export markets as a route to getting more fx.

The big question is whether the Egyptian government can liberalise its economy and how much pressure Gulf states (which lend to Egypt) and the IMF can exert on Sisi. This is his conundrum: if he liberalises the economy against the wishes of the military he risks being replaced, or worse. If he doesn’t there is no real route to economic recovery for Egypt in the short to medium term.

A liberalised economy would see Gulf investors keen to use cheap Egyptian labour as a manufacturing base for the Middle East and North Africa. The exit of the Egyptian military from key industrial sectors such as fuel retail or food manufacturing could lead to a boom in investment, but the relationship between political stability and economic growth is not linear: the kind of political reforms needed to loosen the military’s control of the Egyptian economy are not likely to be forthcoming. The military has run Egypt since 1952, with the exception of the brief interlude of the Morsi government after the Arab Spring.

As such, the short term forecast doesn’t look positive, although it is reasonably stable. While Egypt’s role as a power broker in the Middle East is much diminished, the US, Israel, Saudi Arabia and the UAE all have vested interests in maintaining that stability, especially so given events in Libya and Sudan.

The challenge for FMCG businesses is how to work with a local distributor that can get to the head of the queue for fx and navigate registration blocks. And also how to adapt to considerably lower purchasing power among consumers and the issue of affordability.