A rule Trendtype analysts learned early was that if you want to track supermarket chains in Africa, you had to do it store by store, location by location. It didn’t work to take what supermarkets published at face value: most didn’t keep the information up to date and often would announce the same new supermarket in with different descriptions, making it hard to verify what was going on without tracking at the location level.

Some supermarket chains don’t have a website and oddly mysterious in this digital age about where all their stores are. Among them is Kazyon, the Egyptian discounter that was founded in 2014 and has traditionally gone head to head with Turkish Lidl-alike discounter BIM in Egypt.

The Kazyon growth story

Kazyon opened almost 160 stores in its first two trading years and It opened its 200th store on July 5th 2017. It said it wanted to have 300 stores by the end of 2017 and 1,000 stores by 2025. Then the growth slowed.

For BIM, the leadership in Turkey insisted margins improve before it would open more stores and it stuck on around 300 outlets. Kazyon continued to grow and by the time it attracted a $165m investment in April 2023 it had 600 stores in 600 governates.

This is where things get really interesting.

2023 has been a difficult year for the economy in Egypt: the army retains its grip on the commercial sector, much to the annoyance of the IMF and would-be investors from the Gulf, eager to invest petrodollars. Retail has struggled against a backdrop of currency devaluation, fx shortages, inflation and reduced consumer spend.

Normally this level of economic problems slows or stagnates the growth of supermarket expansion, as indeed has happened for many of Kazyon’s competitors. For Kazyon, this is what’s happened:

- Last 3 months: 152 stores opened

- Last 6 months: 222 stores opened

- Last 12 months: 255 stores opened

Quietly, Kazyon is expanding its store network in Egypt at a pace that is unheard of in Africa. To put this in perspective, there are fewer than 1,000 supermarkets in the whole of Nigeria. Kazyon’s accelerated growth has gone virtually unnoticed, perhaps because so much else is going on in the Middle East. It has a strong echo in how BIM took over Turkey in the 1990s with very aggressive copy+paste store expansion.

The net result is that as at today, Kazyon has 845 stores. Next month it will probably have 875 stores. At the current rate of growth, by the end of this year it will have almost 1,200 stores.

What Kazyon’s growth tells us

Kazyon’s expansion:

- Reshapes the supermarket landscape in Egypt, especially in smaller cities where the likes of Majid al Futtaim, Al Othaim, Panda and Spinneys don’t have stores

- Provides are relatively rare example of a supermarket operator in an African market that can scale rapidly. [It is yet to be determined if that scale is sustainable, but we assume it is]

- Validates the discounter model in more developed African markets.

The discounter model of limited SKUs, a more basic store environment, every day low value (EDLP) is very under-used in African markets. Many markets cannot support discounters: the supply chains simply are not mature enough to enable an EDLP model (which, in practice, means fewer imported products and more domestically processed ones).

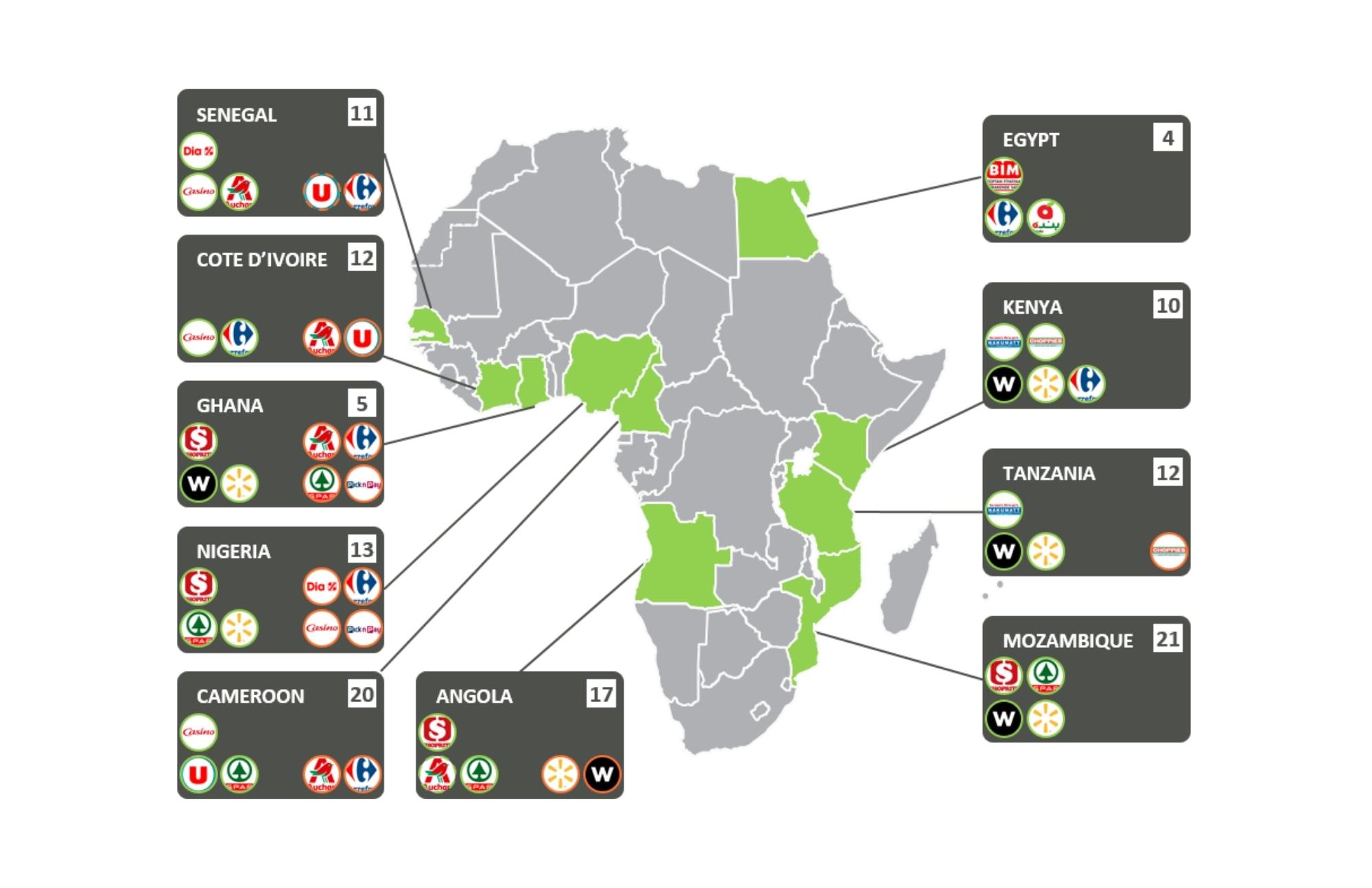

But several markets can support discount supermarket chains: notably in southern Africa, where Massmart (Walmart) has been a presence for decades. Also Egypt, Morocco, Tunisia, Algeria, Kenya, Cote d’Ivoire, Senegal, Cameroon and Angola. In the near term, Ghana, Nigeria, and possibly Ethiopia, Tanzania.

The emerging discounters

There are already emerging discounters: BiM is well established in Morocco and Egypt. Carrefour’s Supeco hybrid discounter format operates in Morocco, Egypt, Cote d’Ivoire, Senegal and Cameroon. The former COO of Naivas in Kenya, Willy Kimani, has just launched his own discounter chain, Jaza. But we would emphasise that in bricks and mortar retail, the discounter format offers huge potential. At a time when governments are pushing domestic food processing and consumers are looking to keep food bills low, discounters offer a solution.

To some extent, discounters already exist, but not in a model we would recognise: the B2B and B2C platforms like MaxAB, Twiga, Copia, TradeDepot, Omnibiz and Alerzo want to offer everyday low prices. They don’t want the costs and complexities of importing goods. They focus on a limited range of the most popular SKUs.

With upwards of 100,000 traditional retailers in their networks in some cases, online B2B/B2C platforms are attempting to be hard discounters in all but name. The growth of social selling/break bulk platforms like Pricepally or Kapu that offer bulk discounts are an online version of the consumers who go to a cash and carry, buy in bulk and split the purchase with friends or family.

The future of discounters is hybrid?

Ultimately, the demand exists for discounters will continue to grow. The fundamental challenge is one of supply chains, profit margins and a replicable, efficient store model. Countries with fluctuating exchange rates or devaluing currency can still support discounters but only if there is a strong enough local food processing sector to provide the core SKUs that discounters stock.

This is why we see discounters emerging in francophone markets with stable currencies and also why their growth will be somewhat limited until the domestic processing sector can reach a tipping point of scale (i.e. discounter are not dependent on imports).

Into this, the AfCFTA and its promise of frictionless trading between African markets is also important. The fewer trade barriers, the more likely we are to see the growth of the modern trade generally and especially the discount retail sector. The sustainable scaling of the B2B and B2C platforms is a bellwether for discount retail. In crude terms, grocery buying platforms develop the back end of discount retail but leave the front end to independent traditional retailers. Discount chains own the process (and the risk) end to end.

The next two years will shape the future of the buying platforms as they seek a route to break even. Investors are providing some funds to support survival not growth. As we have seen with the acquisition of MaxAB by Wasoko and the new investment in Twiga from the family fund that controls French supermarket chain Auchan, there is plenty of headroom to shake things up.

Two interesting examples stand out: the acquisitions of the Haltons and MedPlus pharmacy chains by Ghanaian pharma buying platform mPharma; the launch of bricks and mortars stores by Moroccan buying platform Chari (whose sister company is major FMCG distributor Dislog). We’re not saying the future of discounters will be hybrid, but it could be. The buying platforms offload some of the expansion risks and costs to independent retailers and lay the ground for small format discount because the platforms modernise supply chains in a way that is less obvious than a retailer that goes out and opens up a 50 store retail network.